History, as a discipline, is deeply concerned with time. Understanding how events unfold and how societies change over time requires not only the collection of historical facts but also a method for organizing and interpreting those facts. This is where chronology and periodization come into play. These two concepts are fundamental to how historians analyze and present the past.

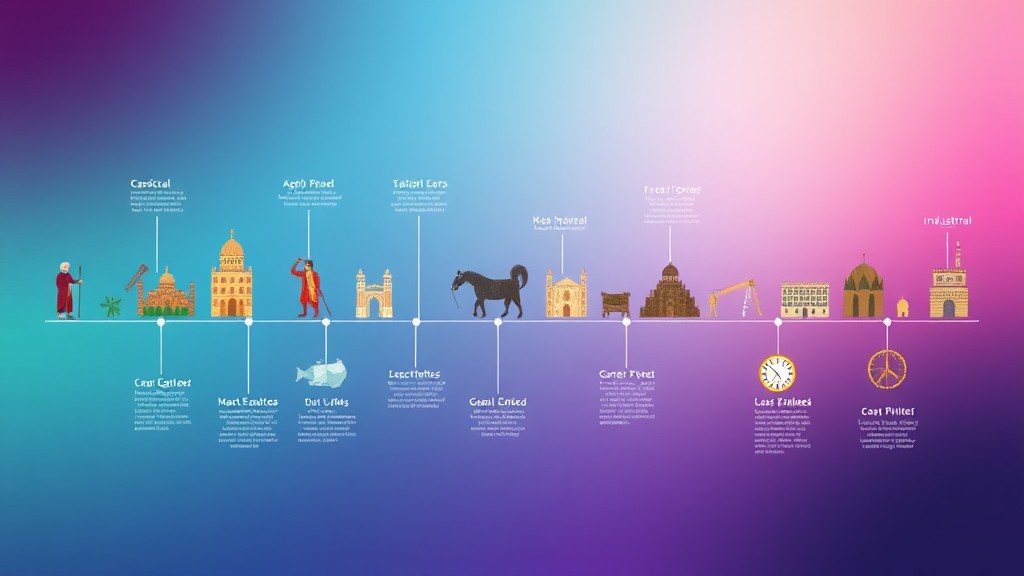

Chronology refers to the arrangement of events in their order of occurrence, helping to create a timeline of history that shows cause and effect, development, and change. Periodization, on the other hand, involves dividing history into distinct blocks of time—periods or eras—each defined by significant events, trends, or themes that distinguish one period from another. Periodization allows historians to categorize the past in ways that make it easier to study and understand patterns of change, continuity, and disruption over time.

In this article, we will explore the concepts of chronology and periodization, how they are used in historical research, and their importance in shaping our understanding of the past. Through examples from various periods of history, we will illustrate how these methods help historians make sense of complex historical narratives.

Chronology: The Framework of Historical Events

At its core, chronology is the science of arranging events in the sequence in which they occurred. This systematic ordering of events allows historians to understand how one event might lead to another, creating a cause-and-effect relationship that is critical to historical analysis. Chronology provides a framework for interpreting history, whether the focus is on a specific event, such as a war or revolution, or on broader historical trends, like economic changes or technological advancements.

The Importance of Chronology

Without a clear chronology, it would be difficult to understand the connections between events or the development of societies over time. Chronology helps historians identify patterns, such as cycles of war and peace, periods of economic boom and bust, or the rise and fall of civilizations. It also reveals how ideas, technologies, and cultural practices spread from one society to another through time.

Chronology is essential for:

- Understanding cause and effect: Knowing the order of events allows historians to trace causes and effects in history, such as how the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand led to the outbreak of World War I.

- Tracking development over time: Chronology helps us follow the development of long-term processes, such as the evolution of political systems, economic practices, or social institutions.

- Establishing historical context: By placing events in their proper chronological order, historians can better understand the social, cultural, political, and economic contexts in which those events occurred.

Example: The Fall of the Roman Empire

One example of the importance of chronology is the study of the fall of the Roman Empire. Historians have long debated when and how the Roman Empire collapsed, and establishing a clear chronology is essential to this debate. Some point to the Sack of Rome by the Visigoths in 410 AD as a key moment, while others argue that the fall was a more gradual process, culminating in the deposition of the last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, in 476 AD.

A chronological study of the events leading to Rome’s decline shows a series of internal and external pressures, including economic troubles, political instability, and invasions by barbarian tribes. Without understanding the sequence of these events, it would be difficult to grasp the complex factors that led to the empire’s fall.

Periodization: Dividing Time into Eras

While chronology provides the order in which events happen, periodization is the practice of dividing history into distinct blocks of time, often called periods or eras. Periodization helps historians group together events, movements, and developments that share common themes or characteristics, making it easier to study and analyze the past. These periods often reflect significant changes in politics, culture, society, economics, or technology.

Periodization is not just about setting arbitrary dates but involves interpreting history in a way that highlights important transitions, such as the shift from ancient to medieval times, or from the medieval period to the modern era. Each period is usually defined by major historical markers, such as wars, revolutions, or the rise of new political systems.

The Purpose of Periodization

Periodization serves several important functions in historical study:

- Simplification: It simplifies history by dividing vast expanses of time into manageable segments, making it easier for historians to focus on specific themes or developments within a given period.

- Highlighting change and continuity: Periodization helps historians emphasize periods of change (such as the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance) as well as periods of continuity, where certain cultural or political practices remain stable over time.

- Comparative analysis: By defining distinct periods, historians can more easily compare developments in different regions or societies during the same era. For example, the Renaissance in Europe can be compared to the Ming Dynasty in China, even though these societies were geographically distant.

Example: Periodization of European History

One of the most well-known examples of periodization is the division of European history into three broad periods: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. These periods are further divided into smaller sub-periods, each reflecting significant social, political, and cultural changes.

- Ancient History (ca. 3000 BCE – 476 CE): This period covers the rise and fall of the great ancient civilizations, including Ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. It ends with the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE.

- Medieval History (476 CE – ca. 1500 CE): The medieval period, or the Middle Ages, spans from the fall of the Roman Empire to the beginning of the Renaissance. It is often divided into the Early Middle Ages (also known as the Dark Ages), the High Middle Ages, and the Late Middle Ages. This period is characterized by feudalism, the rise of the Christian Church, and the formation of European kingdoms.

- Modern History (ca. 1500 CE – present): Modern history begins with the Renaissance and includes the Reformation, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, and the rise of nation-states. It also covers the major political and social revolutions, such as the French Revolution and the American Revolution, as well as the two world wars and the development of globalized economies in the 20th and 21st centuries.

This periodization allows historians to focus on specific transformations in European history, such as the development of capitalism during the Industrial Revolution or the rise of democracy in the wake of the Enlightenment.

The Challenges of Periodization

While periodization is a valuable tool for organizing historical time, it also presents certain challenges. History does not always fit neatly into periods, and the boundaries between eras are often blurred. Major changes in society, technology, or culture do not occur simultaneously across the globe, which means that while one region may be experiencing dramatic changes, another may remain relatively stable.

For example, while the Renaissance is often seen as the beginning of modern history in Europe, many parts of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa or the Americas, did not experience similar cultural or intellectual movements at the same time. Similarly, the Industrial Revolution took place earlier in Britain than in other parts of the world, meaning that periodization based on European history may not apply universally.

Alternative Periodizations

Because periodization can reflect different cultural and regional perspectives, historians often develop alternative frameworks for organizing time. For instance, Chinese history is traditionally divided into periods based on the ruling dynasties:

- Shang Dynasty (ca. 1600 – 1046 BCE)

- Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE)

- Qin Dynasty (221 – 206 BCE)

- Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE)

Each dynasty represents a period of political and cultural development unique to China, and this dynastic framework is a form of periodization that reflects Chinese historical experience.

The Relationship Between Chronology and Periodization

While chronology and periodization are distinct concepts, they are closely related and often work together to provide a comprehensive understanding of the past. Chronology gives us the sequence of events, while periodization helps us categorize and interpret those events within broader contexts.

For example, when studying the Industrial Revolution (typically dated from around 1760 to 1840), chronology tells us when key inventions—like the steam engine or the spinning jenny—were introduced. However, periodization allows us to place the Industrial Revolution within a broader historical context, highlighting the social, economic, and political changes that marked the transition from agrarian economies to industrialized societies.

In this way, chronology helps us understand what happened and when, while periodization helps explain why certain changes took place and how they fit into the larger historical narrative.

Conclusion

Chronology and periodization are two fundamental tools that help historians organize and interpret the vast expanse of human history. Chronology arranges events in their proper sequence, allowing historians to trace developments, identify causes, and establish historical context. Periodization, meanwhile, divides time into meaningful units, helping historians understand patterns of change and continuity over time.

By using these methods, historians can make sense of complex historical narratives, highlight significant transformations, and draw connections between different regions and periods. While both concepts have their limitations—such as the potential for oversimplification or regional biases—they remain essential to the study of history, providing the framework needed to explore the human past in all its richness and complexity.